One of the Biggest Disconnects in Business

Author of The Operations Advantage, Nigel Slack, discusses the formula behind building operations capabilities and getting results across the business

The idea of ‘the learning organization’ has become something of a cliché, yet it is a powerful idea. From 1990, when Peter Senge first coined the phrase to articulate his vision of an organization with groups of people who are continually enhancing their capabilities, the idea has been profoundly influential. Probably because of this, there is plenty of good advice from academics and consultants on how to encourage the development of a learning organization. However most of the advice focuses on the behavioural and cultural aspects of learning, and it misses one important and fundamental issue: if we are to learn in order to make ourselves better, what exactly is it that we are supposed to learn from? What are the specific instances that provide the opportunity to learn?

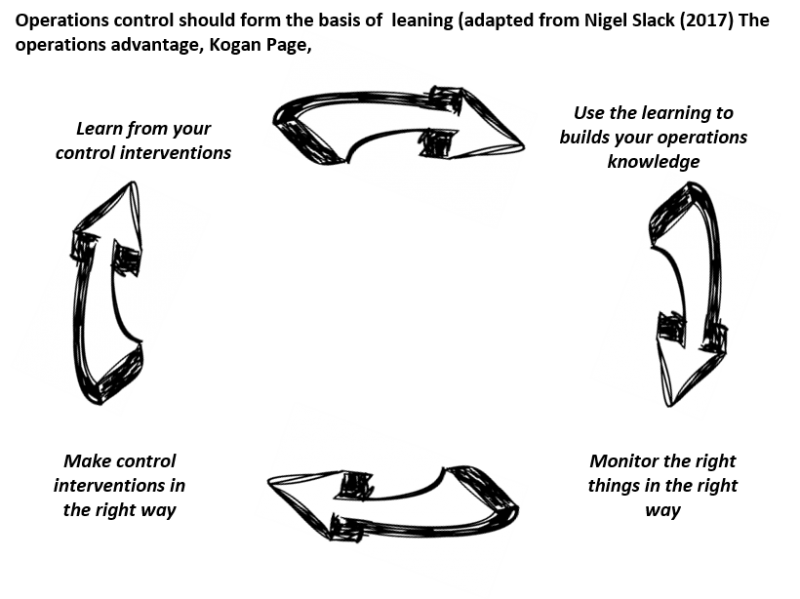

The answer is based on an idea that lies at the core on how we manage operations. All operations need to be controlled, and that control provides one of the best opportunities for operations to learn and build their capabilities. Alas it is an opportunity that is too often wasted. In fact, it is one of the biggest disconnects in business: we fail to associate the routine business of controlling our resources and processes with how we learn and improve. Partly this is because operations control is one of those things that many of us only notice when it goes wrong. It is on the background, like the thermostat that controls the heating in your room. We seem to take control for granted, and in doing so we fail to realize its true significance. But, if operations control and operations improvement are managed so that they are mutually supportive, the learning logic can go something like the image below.

Control means monitoring your operation’s outputs and activities and intervening in the operations’ inputs and activities. Making interventions in your operation allows you to observe the effect of that intervention. You can associate the effect the intervention has on what you did or how you did it. This cause-effect means that you have the opportunity to learn about what reaction an intervention has. Repeatedly learning from these cause-effect observations allows you to build a progressively greater level of knowledge about how your operation works. And with a high level of operations knowledge you can more accurately target what you need to monitor, which allows you to intervene in your operation more effectively. It is cycle that forms an important part of any form’s learning logic.

But don’t dismiss this learning logic as being only an operational issue. See how one COO gained strategic advantage from harnessing routine control:

‘Looking back, we had no real concept of the power of control and the operation was allowed to drift. Our culture said, “If it’s within specification then it’s OK,” and we were diligent in not shipping out-of-spec product. Luckily for us, some of our customers insist on getting our process data, which enabled them to see exactly what is happening right inside our operation. We were also getting all the control data but none of it was being internalized. When we started to focus on what their control data was telling us, we realized what we had been neglecting. Just look at the long-term strategic result of what is essentially a mundane operational issue – production control. Better customer service secured future revenue; operating costs were lower; utilization was higher; product development was less concerned with short-term issues; more professional purchasing made us easier to do business with; and staff retention improved. People know when they are working for an improving business.’

Getting this kind of benefit from your control processes does not come automatically. Grafting this learning cycle onto your planning activities needs to be done without disrupting the primary control task, yet needs to fully exploit the learning potential. To do this, four questions need to be answered:

- Are you monitoring the right things in the right way?

- Are you making control interventions in the right way?

- Are you learning from your control interventions?

- Are you using the learning to build your operations knowledge?

And all these questions should be at the heart of how all operations are managed. It is yet another reason for more sophisticated, more prominent and more effective operations management.

About the author: Nigel Slack is Emeritus Professor of Operations Management and Strategy at Warwick Business School and the former head of its Operations Management Group. He acts as a consultant in many sectors, including Financial Services, Utilities, Retail, Professional Services, General Services, Aerospace, FMCG, and Engineering Manufacturing.

Click the button below to purchase The Operations Advantage, and use code BLGTOA20 to get 20% off your purchase.