7 Unconventional Principles Utilized by Tesco

Tesco has, mostly, been a very successful retailer over the last 25 years or so. They have won the approval of millions of customers, both in the UK and from their operations in many countries, by “creating value for customers to earn their lifetime loyalty”.

There are seven guiding principles which, in our view, underpin Tesco's decision-making. They are, for the most part, unconventional and set Tesco apart from their competitors.

Unconventional Principle #1

Conventional wisdom: Efficiency wins. Tesco's belief: No, effectiveness wins.

Tesco’s primary focus for over 25 years has been to improve its effectiveness in providing for its customers; efficiency targets are important, but always secondary to its primary aim of striving for effectiveness.

Under former CEO, Sir Terry Leahy, Tesco built this culture in how it thought and operated by put effectiveness first and letting efficiency enhancements follow. This approach was integrated into the Tesco business through its ‘Better, Simpler, Cheaper’ principles.

In the modern Tesco, under their current CEO Dave Lewis, the same thinking is applied, with a strong emphasis on any improvement agendas occurring within a strict financial discipline framework. In summary, Tesco has believed and still believes that its quest for efficiency should not destroy effective value creation and delivery.

So, for example, 100% product availability (an effectiveness measure) is the primary supply chain goal while any efficiency improvements from developments in the supply chain can be fed into better prices, which leads in turn to higher sales volume.

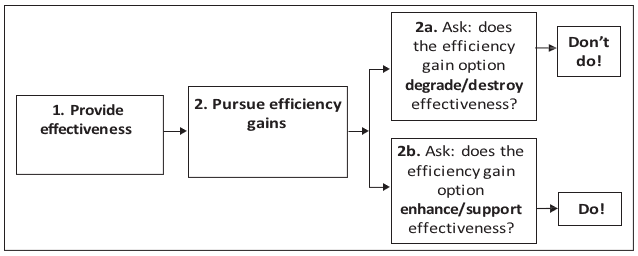

Figure 1 shows how Tesco avoid the “unintended consequences” often associated with so many business improvement initiatives. If efficiencies are pursued in spite of, rather than in keeping with, the effectiveness agenda, the consequence will be that any successes achieved could be short-lived and therefore unsustainable. Thus the pursuit of efficiency is within the effectiveness agenda, not at the expense of it.

Figure 1: Efficiency gains should follow effectiveness provision

Unconventional Principle #2

Conventional wisdom: Deal with complexity. Tesco's belief: No, keep it simple!

A hallmark of the Tesco approach, clearly as discernible today as it was back in the times of Sir Terry Leahy’s leadership, is the art of ‘Keeping it Simple’. Tesco has an inherent belief in being clear and simple in the way the company works and operates. In short, it believes that making things simple wins, not coping with or adding to complexities.

Again, Tesco’s “better, simpler, cheaper” principles identified under Leahy clearly included pursuing simplicity, which was based on de Bono’s (1998) ideas. Leahy felt this was critical in a business as fast-moving and dynamic as Tesco’s: ‘Simplicity is the knife that cuts through the tangled spaghetti of life’s problems’, he said (Leahy, 2012).

Tesco’s current CEO, Dave Lewis, thinks in exactly the same way. Under the heading, “Keeping it Simple”, he summed up the business in a few, clear lines:

"Our business is organised around the three pillars of Customers, Product and Channels. The way we work now is much simpler and clearer. At Tesco, we focus on the little things to make a big difference. Customers are the priority. We place them at the centre of everything we do to deliver our purpose - serving shoppers a little better every day."

The result? All Tesco colleagues completely get what Tesco is about and what the company is trying to achieve.

Complexity is the nemesis of modern organizations. What a simplicity ethos does is distil objectives down to their bare essentials, enabling clarity and then consistent evaluation, decisions and operational delivery.

Unconventional Principle #3

Conventional wisdom: Focus on the competition. Tesco's belief: No, focus on self-improvement.

Conventionally, business leaders are advised that if they want to improve it pays to look at their competitors and learn from the best. Certainly, having an external focus is not a bad thing. It provides objectivity and an ability to begin to see the organization as others see it. Tesco’s view, however, is that a leader’s view should be on self-improvement against purpose - getting better at providing for customers.

Customers do not see the outcome of one function, or one organization when they interface with a supplying company, such as Tesco. They interact with the output of many functions and many organizations all joined up by supply channel processes. It is the output of these processes that customers engage with when transacting with an organization. Tesco gets this. It sees that customers can choose to interact with the output of this system, or not if they feel they can get better value from an alternative supply chain systems’ output.

So, Tesco, while not being unaware of its competitors, sees that its main purpose is to orchestrate and manage its supply chain channels systems to the best of its ability to best serve its customers.

The company realises that not all solutions can be enacted straight away. Instead, it identifies the ‘chosen few’ that will best take the business forward over the coming period to achieve its operating plan priorities. This attention to detail chimes with what Spear (2009) argues is a key virtue of his ‘high-velocity organizations’:

"They specify in advance what outcomes are expected; who is responsible for what work in what order; how products and services, and information will flow from the person performing one step to the person performing the next step, and what methods will be used to accomplish each piece of work... everything it knows so far into these specifications to maximize the likelihood that people will succeed."

Unconventional Principle #4

Conventional wisdom: Make a business case. Tesco's belief: No, if it is right, just do it.

Sometimes decisions are not easy to take for any organization. Determining what is pursued at Tesco, though, is never ad hoc. Decisions are taken in a purposeful, well-thought-out manner and backed by evidence from trials or hard results before commitments are made to progress.

However, there are times when decisions cannot be made in this way; intuition and judgement come more into play. Often the payback from an investment does not return directly on to the bottom line. On these occasions Tesco uses a simple maxim that fits entirely with its corporate philosophy: if it feels right for the customer then it can make business sense too. Examples include:

- 24-hour store openings

- Moving into the convenience market

- Same day delivery services

Unconventional Principle #5

Conventional wisdom: Business is hard to explain, easy to do. Tesco's belief: No, business it easy to explain, hard to do.

Leahy (2012) argued that, on reflection, the company’s values provided a ‘compass’ that ensured the right decisions were taken under his leadership. By listening to customers, he suggested, much can be learnt: ‘heed their advice, however difficult it may be, and you stand a greater chance of success’ is how he concludes Management in 10 Words (Leahy, 2012). Certainly, this is a key element of the Tesco jigsaw of success that is discernible under Lewis too. It all starts with an obsessive focus on the customers is the repeated mantra of both the Leahy and Lewis Tesco’s.

The key was that this was done completely rather than through any tendency to pick and choose. Thus, the argument was to focus not just on tools, not just on just-in-time (JIT) and flow, but on both pillars of the ‘House of Lean’ – JIT and Jidoka.

Figure 2: House of Lean

A business, with its wider supply chain (suppliers, customers and connecting mechanisms), is a complex system. Improvement of that system has to be systemic to become sustainable. Tinkering with parts in isolation aimed at efficiency improvement runs the risk of worsened efficiency, unintended consequences and transient improvement at best. So, start by addressing system purpose to avoid this and create a compelling counter-approach to the quick-win mentality favoured by so many. This means expecting to invest in advance of sustained improvement, for example by raising workforce capability and general skills training, both generic and technical.

Tesco has been brilliant at identifying and tackling the major and recurring problems first before more minor, often quite normal, fluctuations in performance are considered (Evans and Mason, 2011b). Figure 3 shows how reacting to common-cause variation within lower and upper control limits is wasteful tampering.

Figure 3: Fluctuating Performance which can be expected in typical business metrics

So, put simply, Tesco conceives of its business as a complete system. It is driven by its core purpose, which in turn drives its goals. These are delivered via its strategy, using its values and principles. It aims, in all its operations, improvement activities and projects, to continually focus on delivering this.

Unconventional Principle #6

Conventional wisdom: Either be cheapest or innovative. Tesco's belief: No, complete through both price and innovation.

For many organizations, the classic way to improve is to adopt a business model that facilitates the achievement of competitive advantage through efficiency improvement. Michael Porter (1985) has written extensively on how businesses can choose to compete through low prices supported by highly efficient operations, often spanning organizational boundaries through aligned actions with other supply chain members. This can be visualized as in Figure 4, which shows efficiency improvements incorporated into business strategy and deployed into operations.

Figure 4: Using efficiency improvements counter-intuitively

A weakness of this conventional approach is that for many businesses improvement is often not sustained and rarely seems to be reflected in bottom-line gain. This is, as Ackoff (2010) describes, ‘doing the wrong thing righter’. Driving business improvement to achieve cost reduction is missing the point.

The alternative, Porter (1985) espoused, is to compete through a differentiation strategy, the aim being to create uniqueness in the industry which is valued by your customers. However, are customers willing to ignore the price that they are paying, even though they may be attracted by the uniqueness that a supplying organization may have achieved? In the UK grocery sector where competition is fierce and consumer spending power is generally squeezed, notably in the post-financial crisis 2007-2008 decade, it is very rare for a pure differentiation strategy to win out.

Instead, what Tesco’s experience shows is that improvement is about innovation combined with an approach identifying critical constraints and improving against those to achieve sustainable gains. Cost miraculously reduces as well. This is Ackoff’s (2010) ‘doing the right thing’ and is like hitting gold in archery – it doesn’t get any better than this.

This is the counter-intuitive logic behind ‘Lean Thinking’. Cost reduction is seen as an output, not a measure of success on its own. It should not be seen as the primary goal of the company at all. Indeed, cost can be removed from any organization, whether it is trying to compete in the low-cost or the premium differentiated game. From Primark to Rolls-Royce it should be effectiveness first, efficiency second, just as in the blueprint Tesco has generally provided.

A system should be developed to achieve both value and waste elimination, yes, but as a secondary by-product of continuous improvement, which should be the primary goal. This echoes Spear and Bowen’s (1999) finding in ‘Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System’ that suggested that observers wishing to understand and potentially imitate the success of Toyota needed to ‘go beyond the tools and practices… and look at the system itself’.

Tesco has demonstrated that there are synergies in competing on both of Porter’s identified dimensions of competitive advantage, namely price and differentiation. Both can be achieved, contrary to Porter’s view that it is an ‘either/or’ choice.

Unconventional Principle #7

Conventional wisdom: Build from production forward. Tesco's belief: No, act from the customer back.

What is the thinking behind this unconventional stance? In many sectors it used to be convention that supply chains ran at the behest of the manufacturers, which in effect wanted to supply all that they produced to the market on a high-volume, low-unit-cost, ‘push’ model. With intensified competition, catalysed through globalization, deregulation, enhancements in technology such as the internet and so on, there has been an increasing emphasis on the need for organizations to sense and react to customers’ full values and expectations from products and services to earn their custom. Consequently, the view that has been argued for some time now is that the customer should be placed at the heart of process systems improvement.

This stance is summarized well by Meyer and Schwager (2007), who worry passionately about the ‘customer’s experience’ and suggest that managing the customer should not be left to those who have functional responsibility for customer-facing tasks, but should extend also through to all process and functional leaders. They define ‘customer experience’ as the ‘internal and subjective response customers have to any direct or indirect contact with a company’ and argue that each customer’s needs and value net are different and contingent upon the situation they face. They are also dynamic; thus, the voice of the customer needs to be placed centrally in the organization and form the source of all decision making.

Tesco, under Leahy, did exactly this, as we have consistently argued. Now under Lewis, it has returned to the specific Core Purpose orientated around the customer - “Serving Customers a Little Better Every Day”. So, intuitively all Tesco colleagues feel the customer and their experience of shopping with Tesco is intertwined with everything the company represents and is about.

The examples can be exhaustively listed, from the development of ranges for Asian customers to upgrades in the Value and Finest ranges, to the launch of the Goodness brand, providing a range of healthy and nutritious products for children, to the removal of sweets from till aisles.

Conclusion

We have teased out some of the underlying, perhaps less obvious factors that have helped to make Tesco special over the last 20 years or so. Seven unconventional beliefs that characterise the Tesco approach and help it to differentiate it from the competition have been explored - Tesco has tried to become a smarter organization, able to sense, think and act more quickly than its competitors in the cut-throat world of retail.

Tesco uses its obsession to think and act to improve effectiveness, rather than efficiency, to develop and execute unconventional and innovative ideas orientated around serving its customers better and above all keep it all as simple as possible. In so doing Tesco aims to stand out from the crowd. Simple is not the same as easy.

If an organization continues to do what it has always done before, they should not be surprised that they continue to achieve the same outcome. Innovative change, targeted at satisfying customer wants and needs, and sense-checked to ensure unintended consequences are avoided, is the basis of effective delivery and growth towards world-class status.

REFERENCES

Ackoff, R. (2010) Differences that make a difference, Triarchy Press, Axminster

de Bono, E. (1998) Simplicity, Viking, New York

Evans, B. and Mason, R. (2011) What does success look like? Lean Management Journal, 1 (11), July/August pp 7-13

Leahy, T. (2012) Management in 10 words, Random House Business Books, London

Lewis, D. (2016) Tesco Annual report and Financial Statements 2016, Page 12

Meyer, C. and Schwager, A. (2007) Understanding Customer Experience, Harvard Business Review, February, pp 117-126

Porter, M. (1985) Competitive Advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance, Simon & Schuster, New York

Spear, S. (2009) Chasing the Rabbit, McGraw Hill, New York

Spear, S. and Bowen, HK (1999) Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System, Harvard Business Review, September – October pp96 - 106