Supply Chain Simplicity

Simon Eagle, author of Demand-Driven Supply Chain Management, discusses the underlying scientific principles that explain the demand-driven process

An underlying principle that helps scientists in their endeavours to advance understanding of how the world works is that of Occam’s razor: ‘Among competing hypotheses, those with the fewest assumptions should be selected in the development of theoretical models.’

What has this got to do with supply chains? Supply chain management is becoming ever more challenging as performance imperatives increase while, in parallel, supply chains grow in complexity and demand patterns become increasingly volatile (e.g. due to SKU proliferation, fragmenting markets and increasing competitiveness). One consequence is that expensive technology is increasingly being seen as necessary to enable successful management of supply. We have seen this in the past with the arrival of ‘advanced planning systems’, optimization tools (e.g. MEIO) and new forecasting systems (e.g. ‘demand sensing’). We see it now with all the talk of machine learning and artificial intelligence.

It is interesting to note that, despite early high expectations, there is increasing acceptance by many that APS has never really lived up to its promise, and MEIO and ‘demand sensing’ are only able to deliver very marginal, and expensive, performance improvements.

The reason behind this is that all these technologies are sophisticated solutions to a flawed model of how supply chains should be operated. That model is the logic built into DRP, master production scheduling and MRP which calculates, for every component in the bill of distribution/materials what we must move/build/buy is that which we forecast will sell – plus a safety stock for forecast error, less what we already have in stock and in-transit. And, helpfully, this logic alerts planners with exception messages whenever supply schedules are not aligned with the forecast (because, say, the forecast is wrong or has been revised) so that they can interrupt the schedules and make them re-align.

This logic seems, at first, to make eminent sense and can be summarized as ‘plan to make what we think is going to sell’. But Occam’s razor has a caveat that was best articulated by Einstein: ‘Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.’ Additionally, if the original hypothesis turns out to be wrong, an alternative should be sought.

In fact, the ‘plan to make what we think is going to sell’ hypothesis has indeed been found to be wrong, as demonstrated by the level of expediting and firefighting that takes up most of a supply planner's working day - and still they suffer service issues and are left with excessive and unbalanced inventories.

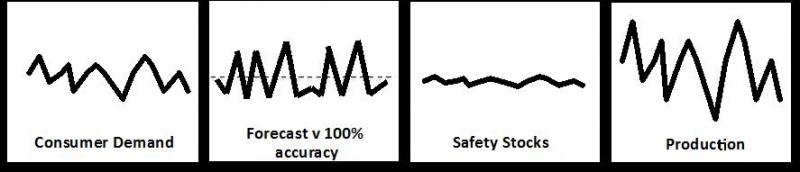

The reason can best be understood with reference to the following diagram that demonstrates how forecast-driven replenishment results in de-stabilised supply and production schedules as the forecast error is blown up the supply chain.

It is these de-stabilised schedules, or supply chain variability, that result in expensive unplanned use of capacity, volatile and increasing lead-times, and ever more unbalanced inventory.

What is the alternative to a forecast-driven supply chain? The answer is that it should be demand-driven because in using a replenishment signal that is, by definition, correct there is no requirement for any subsequent schedule adjustments and all their performance destroying consequences.

A short, and simple description of Demand-Driven Supply Chain Management: ‘the use of multiple correctly positioned, sized and maintained de-coupled inventory locations that are each replenished, using buy/make/ship to replace pull mechanisms, to a stable and predictable sequence, in line with demand (with advanced stock builds for predicted extreme and exceptional events) using simple and low maintenance forecasting techniques for S&OP and inventory target sizing.’

That de-coupled and demand-driven is a far superior model for supply chain management than forecast driven MPS/MRP, is demonstrated by its typical performance improvements:

- Achievement of planned service levels, from

- Between 30% to 50% of the average inventory, with

- Shorter lead-times (up to 80% less), and using

- Significantly less capacity, without

- Expediting, firefighting and no requirement for high levels of item level, short term forecast accuracy

There is little doubt that there are technologies out there that might be able to aid supply chain management but they will only be of genuine help if they recognize that the underlying principle should be that of end-to-end material flow and the most robust process for its achievement is through management of the de-coupled and demand-driven supply chain.